Park Chung Hee

Park Chung Hee was the de facto leader of the May 16, 1961, military coup that ended Korea’s Second Republic. He led the subsequent military junta until 1963. He then transitioned to an elected presidency, holding office until he was assassinated by his KCIA chief in 1979.

Park is a controversial figure in Korean history. On one hand, he is revered by some for his role in modernizing Korea’s industrial sector and kicking off an era of economic hypergrowth. He set Korea on a path of rapid evolution that transformed it from an economic backwater into one of the leading global economies by the 1990s. On the other hand, his increasingly authoritarian rule, marked by the suppression of dissent, imprisonment of political rivals, and executions in the name of national security, paints him as a dictator in the eyes of others. Today, as memories of the poverty and defeatism that Korea faced before Park’s rise to power fade with the passing of older generations, the critical view of his authoritarianism tends to dominate public opinion.

NOTE: Most of the Korean names on this page are spelled in English differently than they would be under the Korean government’s current official Romanization system, which is the system I prefer when writing Korean names. However, since these spellings are how they are known to English-speaking history, I’ve kept them.

Ascension and Consolidation

Park’s early years are covered well enough on Wikipedia, so I won’t go into that here. By 1960, he was an influential general in the Korean Army. The April 19th Revolution in the same year, a student-led uprising, forced President Syngman Rhee to resign after years of corruption and authoritarian rule. This ushered in a period of political instability under Rhee’s successor, Yun Posun, and his Prime Minister, Chang Myon.

Well before May of 1961, there was talk among Korean Army officers of staging a coup. It eventually became an open secret, but the Korean government never acted to prevent it. When it finally did take place, the nominal leader was Chang Do Yong, the Army Chief of Staff, but Park was the driving force behind it. In the aftermath, Chang Myon and other officials resigned, while President Yun remained a figurehead without power. The big question was how the US would react. There’s a great account of the internal discussions surrounding their response in the book about Park in the Additional Resources section below. Ultimately, they decided to work with the new regime.

The coup leaders and the officers who supported them set up the Supreme Council for National Reconstruction, with Chang Do Yong as chair and Park as his deputy. It was during this time that Park began manuevering to consolidate power and eliminate rivals. By July, he had ousted Chang Do Yong and ascended to the council’s chairmanship. For the next two years, with the aid of his nephew-in-law Kim Jong Pil and a cadre of younger officers, Park carried out a purge of officers he perceived as potential threats to his authority.

This purge effectively sidelined most of the top generals involved in the coup. Meanwhile, under American pressure to democratize, Park, who had become acting president following Yun’s resignation in March 1962, reluctantly agreed to hold elections. In preparation, Kim Jong Pil and his associates established the Democratic Republican Party (DRP), covertly populating it with Park’s supporters despite the junta’s prohibitions on political activities.

Park narrowly defeated former President Yun in the 1963 presidential election and won more decisively in their 1967 rematch. He would continue to sideline potential rivals throughout his rule, especially those who were successful in the tasks they carried out for him. Kim Jong Pil, for example, saw himself as Park’s successor and was wildly popular. Ultimately, Park was able to neutralize his influence through political exile. Kim did eventually return to government, but was no longer a potential threat to Park’s authority.

Authoritarianism and Death

In his drive to rebuild Korea’s economy, Park was strongly influenced by the Meiji modernization of Japan begun in the late 19th-century and their slogan of ‘Rich Nation, Strong Army’. At the time Park seized power, North Korea had a stronger economy. He saw the development of South Korea’s economy a critical component of national security. The urgency of economic independence became even more pronounced as US policies shifted during the Vietnam War.

Park was adamant about industrial development as the catalyst for economic growth, leading him to normalize relations with Japan in 1965 to secure reparation funds. As it had only been two decades since Korea’s liberation from Japanese colonial rule, this decision was highly controversial, igniting protests that almost toppled his regime. These challenges, along with others he faced during the 1960s, drove Park towards increasingly authoritarian measures.

After the 1967 election, Park pushed through a constitutional amendment that would allow him to serve a third term, to which he was elected and began serving in 1971. Now his rule took a much more autocratic turn. In October of 1972, he declared martial law, dissolved the National Assembly, and rewrote the constitution to establish a new government. The name of the new constitution, Yushin, or “Restoration”, was inspired by the Japanese Meiji Ishin or “Meiji Restoration”. The document granted Park sweeping new powers, effectively making him president for life.

Throughout the ’70s, opposition to Park’s Yushin government grew as he became more openly autocratic. Public demonstrations became more common and more intense, and the political opposition more vocal. It all came to a head in the aftermath of massive protests in October of 1979.

Kim Jae Gyu had been a loyal Park follower since his first post-coup assignment as commander of the Korean Army’s 6th Division. By 1979, as head of the KCIA, he oversaw the dirty work of torture and other human rights violations that the Park regime increasingly employed. Even so, he advocated for moderation where his rival, Cha Ji Cheol, chief of the Presidential Security Service, pushed for extreme measures. As a result, Kim’s star had fallen while Cha’s had risen.

At a dinner on October 26, 1979, Park, Kim, and Cha had a heated discussion about the recent protests and vocal opposition leader Kim Young Sam. Facing withering criticism from both Cha and Park, Kim stormed out of the room, told one of his KCIA subordinates that “today is the day”, and returned with a gun. While he killed Park and Cha, other members of the KCIA murdered three of Park’s bodyguards and his chauffeur.

The commander of the Security Command, Major General Chun Doo Hwan, was tasked to investigate the assassination. He immediately brought the KCIA under the umbrella of the Security Command, holding the organization fully responsible for Park’s death. Now in complete control of the nation’s intelligence apparatus, Chun was able to initiate a coup of his own the following December by declaring martial law, dissolving the National Assembly, and ultimately becoming president via a blatantly rigged election.

Kim Jae Gyu and his coconspirators were eventually arrested, tortured, tried, and executed.

Saemaeul Undong (New Village Movement)

Saemaeul Undong, the “New Village Movement”, was an initiative Park Chung Hee launched in 1972 in an effort to dampen opposition from the public against his Yushin regime. The word undong means “movement”. Though it originally referred only to physical movement, it has also come to be used, like the English word, to refer to the advancement of shared ideas. For example, “labor movement” in Korean can be directly translated as nodong undong.

Undong also refers to most kinds of physical exercise, such as jogging, hiking, aerobics, and playing sports. Several people have told me about their memories of going outside every morning to exercise to the Saemaeul Undong theme song. So not only was it a movement in the ideological sense, there was actual exercise involved.

The first decade of Park’s rule had been focused on industrial development. With Saemaeul, he was attempting to boost the rural economy and through that to win the hearts and minds of the rural population. At its core was the concept of a “can do” attitude. This was important, as the Korean population as a whole had what some describe as a “can’t do” attitude due to the turbulent and devastating events in the preceding decades. The population as a whole was passive, accepting as their lot in life anything that came their way.

In villages throughout the country, the government set up local committees, staffed by both men and women (really surprising, given the country’s strong patriarchal roots) from the local communities. These committees determined the kinds of development projects that would be best for their communities. The government provided the funding, and the locals did the work. It was massively successful both in terms of the actual projects and in what it did for the national psyche. The “can’t do”, defeatist attitude evaporated. In its place, the Korean people earned a reputation for industriousness and hard work that persists today.

In my video ’Korea Vlog: Kimchi Stew and a Korean Dictator, I visit a restaurant chain called Saemaeul Sikdang, “New Village Restaurant”, to eat kimchi stew and talk about the meaning behind the name. It’s intended to evoke nostalgia for the ’60s and ’70s, though it hasn’t been without controversy.

The company behind the restaurant chain was hit by a storm of online criticism in the early 2010s for playing the Saemaeul theme song in some of its restaurants. The founder, celebrity chef Paik Jong Won, faced accusations that the source of his family’s wealth came through his uncle’s ties to the Park regime, and rumors that his grandfather collaborated with the Japanese during the colonial period.

The company responded to the criticism by stating that the concept behind the name and the playing of the theme was to evoke memories of the ’60s and ’70s. Their aim was to make people nostalgic for the time when the citizenry came together to lift the country out of poverty and improve the quality of life for everyone. They also denied the rumors about Paik’s family history. The storm eventually died down, and Saemauel Sikdang continues to be a popular restaurant.

Today, the word saemaeul alone doesn’t trigger the same response in younger Koreans that it does for their elders. To them, it’s just the word for “new village”, and Saemaeul Sikdang is just a name.

Additional Resources

Books

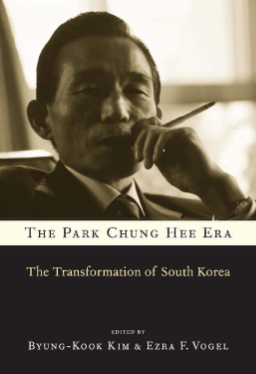

The Park Chung Hee Era

This collection of essays provides a deep dive into Park Chung Hee’s role in transforming Korea from a post-war backwater into a modern global economy. The book examines the political, economic, and military aspects of every stage of Park’s rule, from his post-coup position in the initial military junta to his final years as an unchallenged dictator.

It’s a long read, so it’s not for everyone. I’m unaware of any other such comprehensive analysis of Park, his policies, and key figures in his administration. The stories about Park that I’ve heard from people who lived through the era just barely scratch the surface. Highly informative for those interested in Korean political history. You can purchase it at Amazon. (I may receive a commission for anything you purchase through this link.)

Wikipedia

The Park Chung Hee Wikipedia page has a good overview of Park’s life and rule, with links to articles on other influential people and important events from the era. It’s a great place to start for anyone just looking for a little more detail without committing to a massive tome.